How is it that I have a better Heart Rate Variability (HRV) than Cristiano Ronaldo (below) when he is almost certainly in better cardiovascular shape than me?

How is it possible that my friend regularly has an HRV 30ms higher than mine (about 33% higher) when I am most certainly in better shape than him?

Part of these questions stem from a fundamental lack of understanding of what our HRV actually means. It is not simply a measure of aerobic fitness, although improving aerobic fitness is linked to a higher HRV.

HRV is an interesting topic because of the amount of variability (pun intended) between individuals, sometimes seemingly disassociated from their cardiovascular fitness. I aim to demystify a bit of this, as well as provide a brief understanding of what HRV is and why it matters - some may even claim HRV is the single metric to judge an individuals aerobic health by. Additionally, it’s been brought to mass attention with the advent of Whoop straps and many other tech wearables. Now we dive in.

Heart Rate Variability (HRV) - the Basics

Definition

HRV refers to the average variation in time intervals between consecutive heartbeats, measured in milliseconds (ms). More specifically, it’s the measure of the variation between RR intervals, or the R-Phase when most of the heart is activated resulting in the greatest wave shown by an ECG recording.

Here’s an example:

The RR intervals are the gaps between the big peaks on my poorly drawn heartbeat chart. Notice how the gap varies between beats. With each RR interval, there is a different time gap, resulting in a variability, as measured by the average of the time-gaps.

Instead of beating at a constant rate (with constant gaps between R-phases), the heart adjusts its rhythm based on the body's physiological demands. These small fluctuations are a normal and healthy part of heart function, and reflect the heart's ability to respond to a variety of stimuli including physical activity, stress, and hormonal changes.

Why Does it Matter?

As we just defined above, the literal interpretation of HRV is just the measure of time between heart beats. But it really is a way to find out the state of the autonomic nervous system (ANS). The variation between heartbeat is low in sympathetic activation and high in parasympathetic mode. “Knowing about HRV is one of the best ways to assess the impact of various factors such as; environment, emotion, thoughts, feeling, etc., on the nervous system and how the nervous system responds accordingly (Source).”

This marker of ANS activity comprises the sympathetic ("fight or flight", or activating) and parasympathetic ("rest and digest", or deactivating) nervous systems. A higher HRV indicates a wide ability to adapt to stressors and reflects a dominance of parasympathetic activity. Conversely, a lower HRV suggests reduced adaptability and can indicate higher sympathetic activity or stress levels. It’s typically assumed HRV is a heart rate metric - however that’s just how it is measured. In reality, it is a result of the two competing branches of our nervous systems (Sympathetic vs Parasympathetic). If one of your nervous systems (typically sympathetic nervous system) is dominating, you will have a lower HRV. A fluctuation in our heart rate will result in a higher HRV, which is caused by a balance of our sympathetic system telling our heart to beat faster with our parasympathetic system telling our heart to beat slower.

This all matters because an improved balance in our ANS signifies our body’s ability to respond to our environment and perform well.

A high HRV is a signal that one of your nervous system branches is not dominating - allowing room for the sympathetic nervous system to dominate when it needs to. Whereas a lower HRV could mean you are stressed, fatigued, dehydrated, etc, resulting in an impaired ability to respond to stressors (with the sympathetic nervous system).

HRV Ranges

Of course, now the question becomes what is normal? What is elite, bad, and where do we fall in the world for our gender and age?

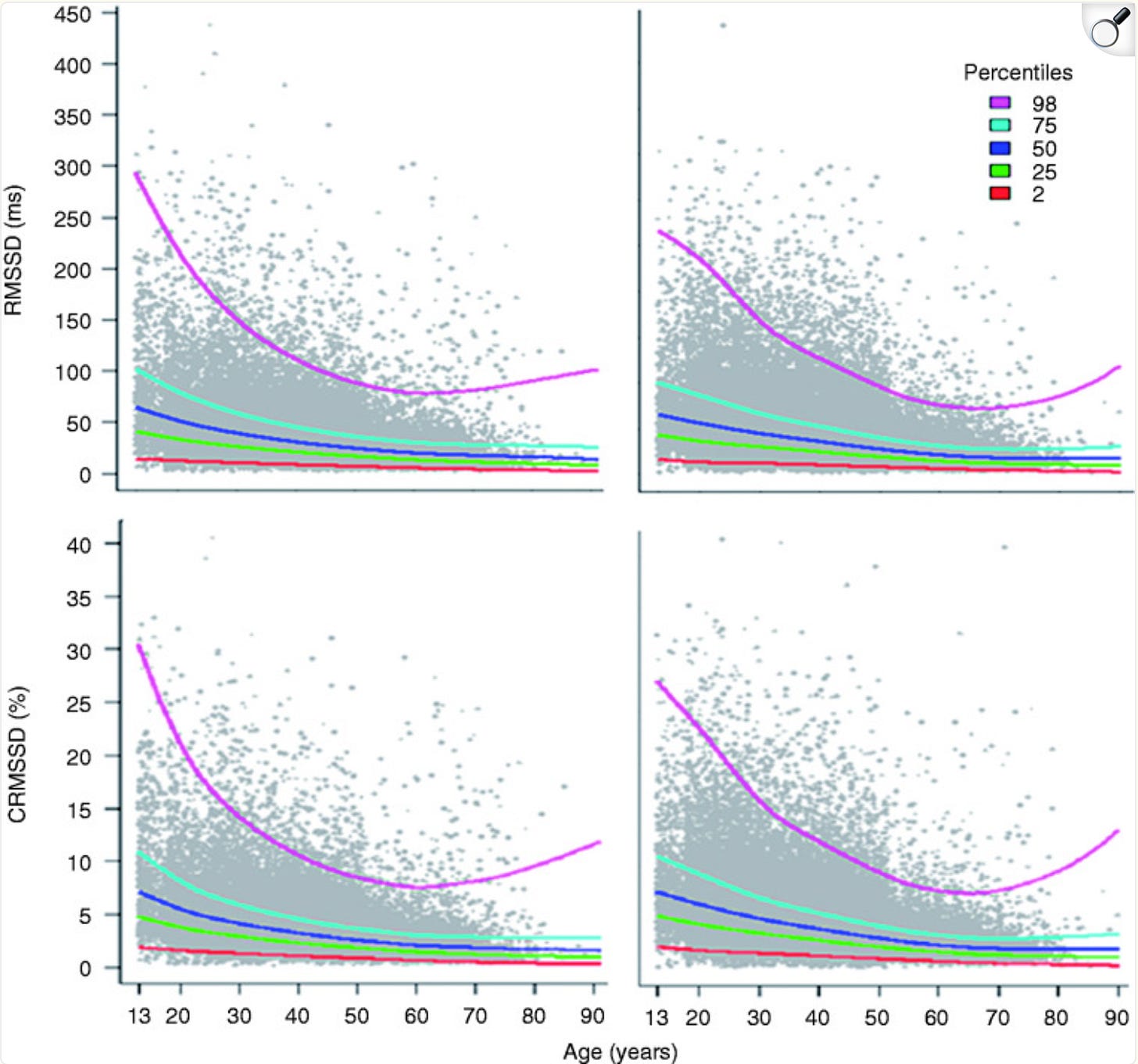

We are in luck. A Netherlands study in 2019 (Tegegne et al. 2019) measured HRVs for 150,000 participants. The below chart shows men in the left column and women in the right. The top 2 (first row) displays the real HRV with lines drawn for RMSSD (root mean square of successive differences), where the bottom 2 are cRMSSD (corrected root mean square of successive differences).

This chart from Training Peaks makes it even easier to understand, by average HRV by age:

You will notice when comparing the two charts, the Training Peaks chart lines up exactly with the 50th percentile lines in the Netherlands study (blue line).

Of course, just measuring off of averages and the rest of the world allows us to fall victim to the “average” fallacy - i.e. just because it is the standard doesn’t mean it is necessarily good. Often times in (American) healthcare we’re judged off of averages, not necessarily what is truly a good metric, regardless of what is being measured.

However, HRV is a truly individual metric that can vary wildly based on a ton of factors. Just look at the first two questions I asked at the beginning of this examination!

That’s why the only thing that matters is you, yesterday. I know that’s a cliche, but especially in health and fitness, it is massively important to measure your personal progress, rather than just compare to a population or people you know.

It is FAR better to measure your progress, especially when you begin to solely focus on improving. And yes, bigger HRV is better if that wasn’t clear from the rest of this write up. An example of measurement is tracking and monitoring for positive changes over a 3-month period.

Factors that Impact HRV

We know what it is, why it matters, and have very specific numbers from a massive population to go off of. But what factors actually influence our HRV?

The National Institute of Health would have you believe your HRV is dependent on pathological, physiological, psychological, environmental factors, lifestyle factors, and genetic factors. While true, that’s incredibly vague.

We want specifics. A few primary factors:

Training

Type of training (strength, steady state, high intensity)

Frequency of training

Intensity of training (including both low and high intensity variations throughout the week)

Recovery - meaning how well you’re able to recover, not overtraining, etc.

Lifestyle

Quality and duration of sleep

Quality, type, and volume of consumption (what goes in your body)

Includes both food and substance use (alcohol in particular)

Hydration - both how much water you consume and electrolyte use

Stress (and stress management)

Other substances (tobacco/nicotine, drugs, etc.)

Biology

Age - as we age our HRV naturally drops

Gender - Women on average tend to have lower HRVs compared to their Male counterparts of a similar age. This is based on averages however, not accounting for your individual blend of genetics, training, and lifestyle

Genetics - some are just predisposed to having a higher HRV

As we see, even from 3 primary factors this breaks down into a ton of aspects. And much of this should be very familiar to my most recent post on Stress Management.

The key takeaway? IT’S ALL CONNECTED. You might have browsed the article on stress management and that was it. But many of the same factors that influence stress also influence our primary bio-markers! Even if you are a “low stress” individual - not accounting for these factors could have negative consequences on other markers, like HRV.

Another thing that’s interesting is the impact of adapting your training and lifestyle for making improvements in HRV.

An example: going for a run elevates your blood pressure. This is a natural result of exercise. BUT, as a result of running, your blood pressure will drop - either back to where it was or even below baseline. This is a momentary benefit of training. And over time, our blood pressure can be expected to experience chronic benefits of exercise (especially if you are not trained and have elevated/high blood pressure). In the moment, exercise will help your BP in the hours/days following the activity. But over a long period of time, your BP will continue to stay low.

The SAME applies to HRV. As explained above, your HRV is just a snapshot of what your ANS looks like at a particular moment. If you are in the middle of a hard workout, your stress will be higher and likely HRV will be lower in the MOMENT.

But, following training you can expect your HRV to recover to baseline. And over time, with appropriate rest/recovery, your HRV will rise above baseline and stay there as you continue training. It’s just like the blood pressure example, except the numbers go in the opposite direction.

Another note - just like blood pressure, your HRV is just a snapshot in time. If you ever went to the doctor and had a lot on your mind, your BP may have been elevated at the time of measurement. In the same sense, you could be feeling stressed right when your HRV is measured (just look at your Whoop). But the only thing that matters is long term trends. Monitoring your blood pressure is an excellent habit to be in as you understand your actual BP - not just a snapshot in time. And monitoring long term trends of your HRV is equally important. Make small (or big) changes and monitor over months and years, not hours and days.

How to Improve Your HRV

I’m going to reference a Whoop article I came across today titled 10 Ways to Increase Your HRV. The 10 are:

Exercise and Train Appropriately

Good Nutrition at the Right Times

Hydrate

Don’t Drink Alcohol

Sleep Well and Consistently

Natural Light Exposure (dawn and dusk)

Cold Thermogenesis (cold exposure for brief periods of time)

Intentional Breathing

Mindfulness and Meditation

Gratitude Journaling

This literally sounds EXACTLY like what I wrote about in Stress Management.

As we’re learning, the factors that influence stress are directly correlated to our heart’s markers. As our HRV trends upwards, you can expect your resting heart rate to trend downwards. But I will break this down by the 3 factors I detailed above: Training, Lifestyle, and Genetics. However for #3, there’s nothing you can do!

Training

Auto-Regulation - This is an interesting topic. Some people are of the mindset that “I have a program, I must STICK to it”. And generally, I’d agree. BUT, if you had terrible sleep, a long workday, are sick, feeling the effects of your last training session, or a ton of other reasons, you may want to regulate the intensity/volume of today’s session. You know your body best. When you get in the gym and the strength just isn’t there. Or you’re feeling extremely gassed, now is the time to do just a bit less. Still push yourself, but not to 100%. Do what needs to be done, and listen to your body.

Functional Overreaching - Some may refer to this as progressive overload. The act of pushing your body during a training session - past your baseline. This applies to both strength AND conditioning. Of course there are side effects - your recovery the next day will be impacted negatively. But with proper rest your metrics will IMPROVE over time. This ties in auto-regulation - know when to push yourself and know when to do a bit less or rest. This is also highly individual. What is overreaching for YOU?

A blend of Zone 2 (steady state), high intensity, and strength training throughout the week. Generally speaking, you should do about 80-90% of your aerobic training in Zones 2-3, and 10-20% in Zones 4-5. If you aren’t familiar, this just refers to your heart rate zone. As the zones increase, this means a higher heart rate during training. Obviously, Zones 4-5 typically mean you are in a high intensity session, whereas Zones 1-3 are low intensity, like walking, hiking, easy cycling, or jogging. Strength training is also dependent on you. Some prefer to lift 5 days per week and are able to recover sufficiently. For me, I prefer to lift 3-4 days per week to allow ample time to recover, especially when I am doing a high amount of Zone 2 and high intensity work.

Your volume of steady state and high intensity is up to you. The NIH recommends a minimum of 150 minutes of low-medium intensity exercise per week. If you want to IMPROVE your HRV, you have to overreach past your previous loads. This is why walking is such a great activity. If you typically get 7k steps per day, aim for 10-12k steps per day. It is an easy way to increase your Zone 1-2 activity during the day with a minimal impact to your need for recovery and rest.

A simple recommendation: lift 3-4x per week, do steady state training 3-4x per week, and 1x high intensity session per week.

Rest and Recovery - Take your rest days, and use active recovery methods as well. An active recovery day could look like a 30-60 minute walk. You get 2 benefits: 1) you just knocked out a steady state session and 2) you managed to do a bit of recovery as well (by not overreaching). But rest is massively important. Listen to your body and take at least 1 full rest day per week.

Lifestyle

I don’t need to outline a ton of specifics here, as it would be a direct copy and paste from the 10 ways to improve HRV from Whoop and my Stress Management article.

BUT, a few key things EVERYONE can manage:

prioritize sleep - and going to bed and waking up at the same time

View morning and evening sunlight (sunrise and sunset)

Eat well, ignore the junk food, reduce sugar intake, and focus on eating quality protein and leafy greens

Drink more water and consume electrolytes

Get rid of alcohol (or at least reduce your consumption). Now, some say a heavy drinker is classified as consuming 2 or more drinks per day, or 14 drinks per week. 2 in a day might not sound like a lot, but 14 drinks in a week is extremely detrimental. Start small, and reduce over time.

That’s it. This should demystify heart rate variability for you. And as we now know, the majority of our HRV is in our control, except for the freaks like my friend who just naturally hovers at 130 despite drinking alcohol. BUT, we are all not the same. And if you want to improve your HRV, I recommend acting on the above factors. To get better, you cannot “maintain”. You have to overreach on occasion, followed by recovery. This is why I’m a firm believer that maintenance is a recipe for a decrease in overall health. If you are not consistently pushing towards a goal, you will fall behind as a result of aging. Time is not on our side when it comes to health, so we have to keep working.

Happy Wednesday.

Cheers.

DISCLAIMER

This is not Legal, Medical, or Financial advice. Please consult a medical professional before starting any workout program, diet plan, or supplement protocol.